Offshore Outsourcing - The Hidden Costs of Transition

The transition period is perhaps the most expensive stage of an offshore outsourcing endeavor. It takes from three months to a full year to completely hand the work over to an offshore outsourcing partner. If company executives aren’t aware that there will be no savings—but rather significant expenses—during this period, they are in for a nasty surprise.

"You have to bring people to America to learn your applications, and that takes time, particularly if you’re doing it with a new vendor for the first time," explains GE Real Estate’s Zupnick, who maintains a handful of three-year contracts with offshore outsourcing vendors, including TCS and smaller vendor LSI Outsourcing. In GE Real Estate’s case, the transition time for each vendor was three months at the very least and up to a year in some cases, in addition to the money-draining vendor selection period of several months.

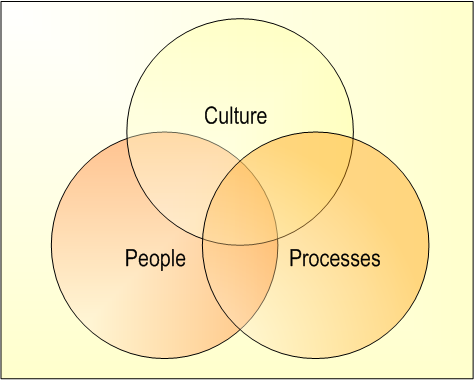

Zupnick, who has seven years of offshore outsourcing experience, says most of his peers don’t appreciate the time and money it takes to get a relationship up and running. "The vendors say you can throw it over the wall and start saving money right away. As a result, I’ve heard of CIOs who have tried to go the India or China route, and nine months later they pulled the plug because they weren’t saving money," Zupnick says. "You have to build in up to a year for knowledge transfer and ironing out cultural differences."

CIOs must bring a certain number of offshore outsourcing developers to their U.S. headquarters to analyze the technology and architecture before those developers can head back to their home country to begin the actual work. And CIOs must pay the prevailing U.S. hourly rate to offshore outsourcing employees on temporary visas, so obviously there’s no savings during that period of time, which can take months. And the offshore outsourcing employees have to work in parallel with similarly costly in-house employees for much of this time. Basically, it’s costing the company double the price for each employee assigned to the outsourcing arrangement (the offshore outsourcing worker and the in-house trainer). In addition, neither the offshore outsourcing nor in-house employee is producing anything during this training period.

But it has to be done. "We made a mistake in the beginning of just packing up the specs and shipping them over, looking at it from a pure cost standpoint," says Craig Hergenroether, CIO of Barry-Wehmiller, a packaging manufacturer that has its own development center, Barry-Wehmiller International Resources, in Chennai, India, and works with other offshore outsourcing vendors. "Silly mistakes were made because we didn’t take the time to have them come over. It’s a false savings to keep costs down by communicating only by phone."

During the transition, the offshore outsourcing partner must put infrastructure in place. While the offshore outsourcing partner incurs that expense, the customer should monitor the process carefully. Often it can take longer than expected. "It took an awful lot of time to bridge the Pacific [networking our company to the Indian vendor] and getting that to work correctly," remembers Textron Financial’s Raspallo, who spent six months and $100,000 to set up a transoceanic data line with Infosys in 1998 for Y2K work. It also cost an extra $10,000 a month to keep that network functional. "You have to know hands down that the technology infrastructure you put in place is fully functional and will operate at the same performance level as it would if you were connecting to someone on the next floor. Otherwise, you’ll have a lot of costly issues to deal with."

DHL’s Kifer had similar problems. Long lead times for acquiring the necessary hardware in India delayed development work, he says. The hardware holdup put off the start of offshore outsourcing work for several months, requiring DHL to continue to keep vendor workers employed onsite at the more expensive rate.

During the transition period, the ratio of offshore outsourcing employees in the United States to offshore outsourcing employees working at the vendor’s overseas headquarters is high. But after the transition is complete, CIOs have to get those employees out of the office if offshore outsourcing is to be a money-saving move. "It’s got to be 80 percent or 85 percent working offshore outsourcing or the numbers just don’t work," explains GE Real Estate’s Zupnick.

It makes sense for offshore outsourcing service providers to place as many of their employees in the United States as possible. The provider’s margins—already quite decent for offshore outsourcing work (Indian companies charge U.S. companies $20 an hour for an employee they pay around $10)—really skyrocket when they’re on American soil. "They make more money and often the client feels better having them close," says Praba Manivasager, CEO of Minneapolis-based offshore outsourcing adviser Renodis. "But the customer immediately loses all of the bill-rate savings." If not included in the original contract, additional travel and visa costs also must be figured in. Tally it all up and you will pay as much as you would for one of your own employees.

It’s a difficult area for CIOs to manage. Work is much easier to do with offshore outsourcing workers onsite, but to cut costs they must push as much overseas as possible. Conversely, the more manpower based offshore outsourcing, the more project problems and delays. Barry-Wehmiller’s Hergenroether says the amount of workers you can reasonably send offshore outsourcing depends on the type of work being done. Industry- or company-specific system development requires more developers onsite. Legacy maintenance or simple upgrades may not require a soul.

"On some of our projects, up to 50 percent of offshore outsourcing workers are onshore; on others it’s closer to 10 percent," Hergenroether says. In some cases—where specific skills are the reason for offshore outsourcing—he may even bring in offshore outsourcing talent over long term. "But if you’re going to do that, your cost savings diminish dramatically," he says. In fact, there may be no savings at all.

Bottom line: Expect to spend an additional 2 percent

to 3 percent on transition costs.

By Stephanie Overby

Back Office Fields

- Telemarketing

- Book Keeping

- Data Entry

- Virtual Assistant

- Transcripting

- Call Center Agents

- Email Chat and Support

- Help Desk

- Human Resources

- Proof Reading

IT Fields

- C++

- SQL

- Vb.net

- Web Design

- C#

- Asp.net

- Website Developer

- Java

- I.T Support

- Dreamweaver

General Fields

- Marketing

- SEO Internet Accounting

- Social Networking

- Blogging & Forums

- PPC Internet Marketers

- Technical Support

- Financial Analyst

- Advertising

- and many more...

- Please enquire