Offshore Outsourcing: Quantifying ROI

Read any case study and you'll probably encounter overblown statistics that say offshore outsourcing reduced costs by 50 percent, reduced number of defects in production by 25 percent, reduced time to launch application by 40 percent and so on. Some even go a step further and extrapolate these figures to 'business value'. Example: launch time reduced by 10 weeks implies 10 weeks of additional revenue or reduced costs. So 10 divided by 52, then multiplied by annual revenues or IT annual spend equals business value from reduced launch time. Lo and behold—suddenly you have a number in tens of millions. Add up all the other sources of value and you may reach hundreds of millions and even billions as the business value. Sounds good, right? Especially in this time of recession woes.

But if this was accurate, customers would not be so unsure about whether offshore outsourcing has delivered value. Numerous surveys indicate that anywhere from 17 percent to 53 percent of customers have not realized business value/return on investment from offshore outsourcing. Yes, yes, statistics can prove just about anything, but whatever the number, there are customers who have not realized tangible business value from offshore outsourcing. And this article is for you folks.

When quantifying the business value of offshore outsourcing, customers must consider three important aspects that are often ignored: the appropriate comparisons, the hidden costs and the distinction between theory and reality.

Appropriate comparisons

While building the business case for offshore outsourcing, the most common comparison is between onshore and offshore, apparently in answer to the question "if we had to do the project in any other way apart from offshore, how much would that cost?"

Many assumptions end up wrongly overestimating the onshore cost. Most common is using the same headcount number in both cases. When a project is done onshore, fewer people are required because of reduced activity level in areas like knowledge capture, knowledge transfer, project co-ordination and environment support. Then there is the productivity factor.

"Sath" Sathyanarayan, author of Offshore Development and Technical Support: Proven Strategies and Tactics for Success, says that even if offshore personnel are as competent as the local staff—which is your best case scenario and unlikely to be the case when you are getting started—there will a productivity loss because of systemic issues.

Also, the assumption that all the onshore work will be done by newly hired internal employees may not be the right one to make; customers almost always leverage contractors and existing employees. For the former, use the relevant contractor rates that are likely to get negotiated and the appropriate loading factor (you don't pay pensions, holiday allowances etc. to them). For the latter, consider if they can be treated differently: it could be a sunk cost for a period of time or a partially apportioned cost. Finally, internal employee costs are excessively padded by something called "an overloading factor"—to account for pensions, holidays, desk space, corporate overheads and so on. A figure of anywhere from 20 percent to 50 percent is normally used—choose the figure that reflects reality, and take into account that you can't recover any of those costs anyway.

Hidden costs

The straightforward costs are fairly easy to see—costs related to personnel, communication, IT infrastructure and tools/licenses (though sometimes the uplift required for converting single site to multisite licenses can be hidden).

Many cost elements are not obvious. In Hidden Costs Impact Value in Outsourcing, authors Whitfield and Joslin state that potential outsourcers in all industries commonly assume that outsourcing can be plug and play, that the company will only have to absorb limited up-front costs before large savings can be realized, and that offshoring for labor arbitrage will ensure more than 60 percent cost savings. In reality, 10 percent to15 percent savings is more realistic for highly commoditized service areas, and 40 percent to 50 percent savings can be achieved only in optimal circumstances.

Travel of a customer's onshore staff first comes to mind as a hidden expense: A leading European software provider indicated that it takes 40 trips per annum to manage its offshore product testing program.

Equaterra, an outsourcing consultancy, points out a couple of interesting examples of hidden costs:

- Hidden cost of work retained onshore, internally.

One retailer had outsourced the work of 1,100 employees, but held onto 50 percent of the work for 200 of those employees. As a result, the company overstated its business case by $24 million. - Hidden cost of internal, transitional headcount.

Companies usually don't account for the costs of employees who help in the transition. For example, one pharmaceutical company kept about 20 percent of its staff for six months after the go-live date, which added $1.5 million in cost. Overambitious headcount estimates can cut projected savings by 10 percent to 20 percent. - Other examples of hidden costs are setting up

(initial knowledge transfer, training, retraining

et al) and managing the offshore outsourcing engagement

(governance system, additional personnel, management

time).

A McKinsey study indicates a figure of 10 percent for additional transactional costs and 10 percent for additional monitoring costs, though particular cost elements were not specified.

Theoretical versus actual impact

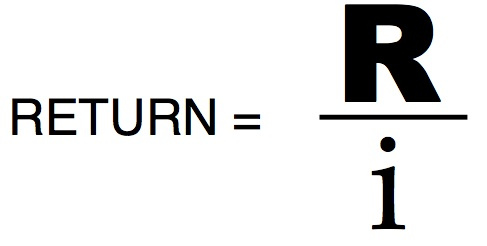

A recent whitepaper by a leading offshore outsourcer in collaboration with a top tier industry analyst, reported that their return on outsourcing model takes into account benefits from cost savings, efficiency gains and revenue improvement. But the bulk of the benefit actually comes from revenue improvement rather than tangible cost savings.

Assumptions on revenue impact are open to theoretical debate, and seldom evidenced in financial statements. It's not that there is no revenue impact for offshore outsourcing, but customers should make the distinction between what benefits will actually hit the books versus benefits that are more theoretical in nature.

Statistics can prove just about anything. You need to exercise diligence and your own prudent judgment in the quantification process, otherwise you will end up building unrealistic, unseen and infeasible expectations of business value from offshore outsourcing.

Arpit Kaushik runs the London-based outsourcing service design firm, Crystals, that helps forward-looking companies to realise the promised benefits of outsourcing.

© 2010 CXO Media Inc.

By Arpit Kaushik cio.com

Back Office Fields

- Telemarketing

- Book Keeping

- Data Entry

- Virtual Assistant

- Transcripting

- Call Center Agents

- Email Chat and Support

- Help Desk

- Human Resources

- Proof Reading

IT Fields

- C++

- SQL

- Vb.net

- Web Design

- C#

- Asp.net

- Website Developer

- Java

- I.T Support

- Dreamweaver

General Fields

- Marketing

- SEO Internet Accounting

- Social Networking

- Blogging & Forums

- PPC Internet Marketers

- Technical Support

- Financial Analyst

- Advertising

- and many more...

- Please enquire